Cenote Diving in the Yucatán

June 25, 2024 · 17 min read · travelAfter a 2.5 year dive hiatus since earning my Rescue Diver certification (a skill I’ve probably lost by now, haha) I finally went diving again! This was my first experience diving in freshwater, and I wasn’t sure what to expect. I didn’t think anything could possibly be more enjoyable than reef diving with schools of fish, turtles and rays, or more thrilling than exploring the USS Spiegel Grove shipwreck off the coast of the Florida Keys. But boy oh boy was I pleasantly surprised. Diving in the cenotes of the Yucatán easily ended up being one of the most unique dive experiences I’ve ever had.

What is a cenote?

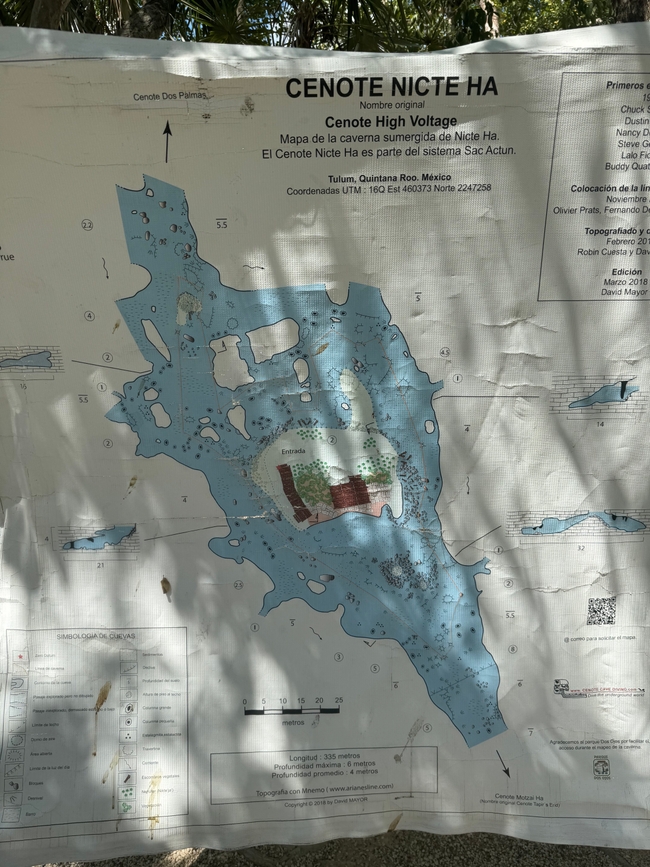

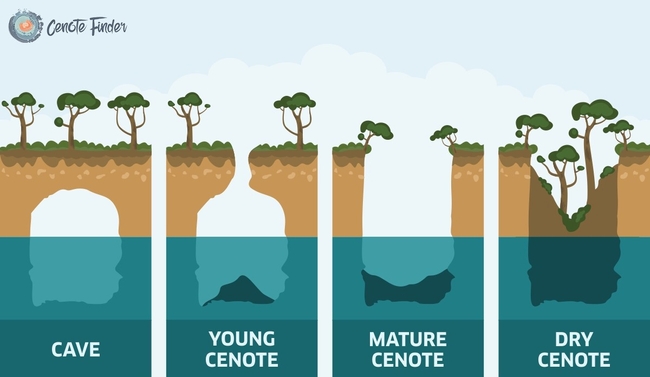

A cenote is essentially a natural sinkhole. They exist in many different shapes (generally differentiated by how recently the cave collapsed), and the image below from Cenote Finder provides a great illustration. The word “cenote” (pronounced seh-no-tay) comes from the word “ts’onot” in the Yucatec Maya language which means “cave with water”.

Different types of cenotes by level of maturity. Photo from Cenote Finder.

The Yucatán peninsula is home to 7,000 cenotes, many of which are connected to each other through underwater cave systems. In fact, the two longest underground cave systems in the world, Sistema Ox Bel Ha and Sistema Sac Actun, are both in the Yucatán peninsula.

In the past, the cenotes played a very important role in the lives of the Mayans. Not only were cenotes their main source of freshwater, but they also considered cenotes to be sacred as they were believed to be entranes to the underworld. This is why many Mayan ruins, such as Chichen Itza and the Tulum Ruins, are located near cenotes. Due to their sacred nature, sacrifices are also known to have been performed in some cenotes, such as the one in Chichen Itza.

What kind of certification do you need to dive in cenotes?

A regular recreational diver license—like the Open Water or Advanced Open Water certifications from PADI or SSI—will do! This is because cenote diving falls under cavern diving, not cave diving. The main distinction between the two is the presence of natural light: it's considered cavern diving if you can see natural light and are no more than 100 meters from an exit. This ensures that if an issue arises, a safe resurface is doable, unlike in cave diving.

Cave diving is an advanced form of the sport. If I had to guess I would say that less than 5% of recreational scuba divers are also certified cave divers. It requires extensive training and is not for everyone (definitely not for me at least!). If you're curious about the specifics of cavern and cave diving, I recommend reading more about their differences here.

It’s important to note that while you’re not required to be a cave diver to be able to explore the cenotes as a guest, you do need to be a certified cave diver in order to be able to work as a scuba dive guide. Guides must also don their full cave diving gear, which typically includes double of everything (e.g. two tanks, two flashlights, etc.). Even though I knew that cenote diving would be completely safe, it gave me an extra level of comfort knowing that my guide is not just a Divemaster, but also a certified cave diver.

What to know before visiting

🧳 What should I bring?

The water in the cenotes tend to run a little colder than the water in the sea (~25°C in cenotes vs ~27°C+ in the sea), which I imagine is due to the lack of sunlight. For this reason, a lot of people wear 5mm wetsuits to keep themselves warm. Our dive package included 5mm wetsuits free of charge, but since I already had my own 3mm wetsuit I decided to wear that for the first dive to try it out (it’s more comfortable wearing your own wetsuit anyways as you know it’ll fit you well… and you know no one else has peed in it, haha). Though it felt noticeably colder than diving in the sea, I felt that my 3mm wetsuit still did a good job of keeping me warm, so I opted to stick with it for the rest of the dives. The only time I somewhat regretted the decision to not wear a 5mm wetsuit was on the day we did 3 dives in a day. By the end of the 3rd dive, I was ready to jump out of the water and soak up the sun!

✋ What should I not bring?

The use of regular sunscreen is prohibited (if not, highly discouraged) at most cenotes since the chemicals from the sunscreen can damage the cenote ecosystem. Not only are cenotes an important part of the Mayan culture and history, but they’re also a part of a fragile environment that includes both the cenote as well as the surrounding flora and fauna. It’s therefore important to preserve them as best as we can. I didn’t feel the need to wear sunscreen anyways since I was wearing a full wetsuit, but if you need to protect yourself from the sun, consider wearing a rash guard instead or using reef-safe sunscreen.

3️⃣ Rule of thirds

When diving with an overhead environment, managing air supply is even more important as resurfacing is more difficult. Therefore, prior to starting our first cenote dive our guide explained to us a safety guideline known as the rule of thirds. It refers to how divers divide their air supply into thirds: 1/3 for entry, 1/3 for exit, and 1/3 for emergencies. How this works in practice is that whenever we’ve used 1/3 of our air (so ~2000 psi or ~133 bar), we need to let our dive guide know so that we can start making our way back to our entry point. Thankfully, most of the cenotes are quite shallow anyways so we were able to be fairly efficient with our air consumption.

💦 What is a halocline?

Cenote water is usually freshwater, but cenotes near the coast are often connected to the ocean, creating streams of saltwater within them. When you see these streams of saltwater in the cenotes they often cause the water to appear blurry. This is because saltwater and freshwater have different densities and salinities, hence different refractive indexes. This meeting point between water of different salinity is referred to as a halocline. Sometimes the different streams of water will also have different temperatures, and this is called a thermocline. Haloclines and thermoclines definitely make for a unique diving experience!

🤪 What is hydrogen sulfide?

In some cenotes, especially those with significant organic material, it’s common to observe a milky-white layer of hydrogen sulfide (H₂S). It forms through the decomposition of organic material such as plants and animals that fall into the cenote. The smell is often described as being similar to rotten eggs, noticeable even when underwater.

📍 Where should I stay?

Most of the cenotes popular for scuba diving are located near Tulum, a town just 80 miles south of Cancún. However, during this trip, my friend Zack and I chose to stay in Playa del Carmen instead. Although it is a bit more developed, we opted for Playa del Carmen mainly because it was more accessible from Cozumel, where we were traveling from. For my next visit to the Yucatán, I would probably consider staying in Tulum instead to shorten the morning commute to the cenotes.

If you’re looking for a dive shop to explore cenotes with, I’d highly recommend Ko’ox Diving! Our guides were incredibly knowledgeable and experienced and I would not hesitate to go diving with them again.

Now, without further delay, here’s the list of cenotes we explored on our trip, presented in the order of our visits.

Jardin del Eden (Ponderosa)

Cenote Eden was the perfect introduction to ease us into cenote diving. Despite having watched numerous cenote diving videos on YouTube, I was still pretty nervous about the idea of diving in an overhead environment. Thankfully, my first cenote dive was not only straightforward but it was also so stunningly beautiful that I was hooked from the start.

This cenote features a large, circular open area with the cavern to the right of the entrance stairs. As a first-time cavern diver, knowing there was an unseen world just beyond where I stood was somewhat intimidating but also exhilarating.

Our dive began with our guide, Victor, leading us on a shallow loop around the open area at about 22 feet deep. This not only gave him the opportunity to assess our skills but it also gave us an opportunity to get used to the equipment and ensure we can get into a neutrally buoyant position. Afterwards, we ventured into the cavern, descending to around 45 feet.

The cavern stretched for about 100 meters. Entering the cavern felt eerie. Although it wasn’t pitch black, we still needed our flashlights to see. Having only done one night dive before, this was a new experience for me and I’m not going to lie, it was a bit unsettling! I also found that juggling both the flashlight and my camera, all while following Victor, was a bit challenging at first, but I soon settled into the rhythm of the dive. Inside, the cavern was full of stalactites which further added to the eeriness. While there wasn’t much marine life due to the lack of sunlight, we did spot a black langostino.

As we approached the end of the cavern, we experienced both a halocline and a thermocline. The warm saltwater contrasted with the cooler freshwater made for a pleasant surprise. The halocline on the other hand creating a blurriness which, although fascinating, was also slightly disorienting! The halocline combined with the stunning sunrays was beautiful to witness.

That moment of seeing the sunrays cast down on the cenote for the very first moment was nothing short of magical!

Going through the halocline was both thrilling and disorienting

Nicte Ha

This cenote offered a distinct experience from Eden. It featured a large pool where you could snorkel amongst lilypads. However, unlike the out-and-back cavern dive at Eden, here our dive route would take us around a cavern encircling the main opening. With a maximum depth of only about 20 feet, it was also a much shallower dive which meant that we didn’t need to do a safety stop at the end.

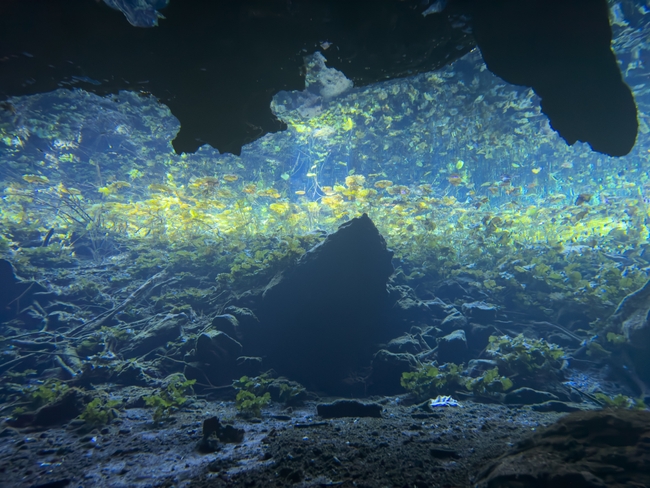

The cavern ceiling was lower, and the floor was more silt than rock, which means that it’s essential to have good buoyancy control to avoid disturbing the silt and thus reducing visibility. Despite the challenges, there were plenty of stunning spots to observe sunrays penetrating the water, making the dive an incredibly beautiful experience!

A glimpse of the marine life in Cenote Nicte Ha

The Pit

This might just be my favorite cenote due to the breathtakingly beautiful sunrays. The sky was cloudy when we arrived which got me worried that we’d miss out on the main spectacle, but thankfully the sun broke through just as we jumped in, casting beams that reached all the way to the bottom of the cenote. Victor mentioned that during winter, these rays stretch more horizontally across the cenote.

Visiting The Pit requires an Advanced Open Water (AOW) certification as most dive shops will take you to 100 feet where you can observe the layer of hydrogen sulfide resembling thin clouds. There were also tree branches eerily protruding from underneath, adding a mysterious touch. Looking upwards from 100 feet you could see the sunrays penetrating all the way to the bottom of the cenote. It felt otherworldly, and it left me speechless…though admittedly, speech isn’t a possibility underwater! I could have stayed there for hours admiring that view.

As we started slowing ascending, spiraling around the cenote, we drew closer to the stalactites decorating the top of the cavern. Altough the stalactites were fascinating to look at up close, the sunrays were still the star of the show. At about 66 feet we also encountered a halocline. The blurry effect from the halocline in combination with the sunrays definitely added to the cenote’s mystique.

Dos Ojos

The Dos Ojos cenotes are part of the massive Sistema Sac Actun—the world’s second-longest underwater cave system. The name “Dos Ojos,” Spanish for “two eyes,” originates from an aerial discovery post-hurricane as two cenotes next to each other resembled a pair of eyes.

Dos Ojos is one of the most popular cenote dives in the area and with the beautifully intricate stalactite and stalagmites, I can completely understand why. Marine life on the other hand is relatively sparse in these cenotes, though we were lucky to spot some goby as well as smaller fish near the entrance of the cenote where sunlight is more readily available.

At Dos Ojos, there are two main lines you can dive: the Barbie Line and the Batcave. The Barbie Line, curiously, features a Barbie doll secured to the line (wish I could tell you why; I forgot to ask Victor about it). Meanwhile, the Batcave line offers a pretty unique dive experience as it leads you into a cave inhabited by bats. Contrary to what one might expect from a cave full of bats, it doesn’t smell bad at all; the fish living in the water underneath do their part by eating the bat poop, thus relieving the cave of any unwanted smell.

Me at Dos Ojos, courtesy of @aqualens_mx

Angelita

Angelita is as eerie as they come. I’m not sure why decided to call it “little angel”, because this cenote was far from heavenly. If anything, it feels more akin to entering a witch’s lair. The cenote is a deep, cylindrical pit stretching down to 115 feet. As soon as we jumped in the water, we started descending. The visibility was relatively poor; not so poor that we couldn’t see each other, but poor enough that we couldn’t see the cenote walls.

At around 100 feet, we encountered a thick layer of hydrogen sulfide. In contrast to the thinner layer we experienced in The Pit, this one was so dense that it looked like sand from certain angles, giving the illusion that the bottom of the cenote was near when in fact there were still a few more meters to go. So we huddled closely, check that our flashlights were on, and continued our descent through the hydrogen sulfide.

As we descended through the layer of hydrogen sulfide, visibility reduced so drastically that I couldn’t even see the faces of the divers around me, even though they were just a couple of feet away. All I could see was the light emanating from their flashlights. It was pretty spooky, and if our guide hadn’t briefed us about this exact experience I would have definitely panicked! But thankfully I was prepared, and after descending through 6-10 feet, we made it out to the other side.

Emerging beneath the hydrogen sulfide felt like transitioning to a night dive. Due to the thickness of the hydrogen sulfide, no sunlight is able to pass through, rendering it pitch black. We also had to be cautious with our buoyancy to avoid disturbing the silt as the floor was no more than 10 feet underneath us. It was littered with leaves, branches and even larger tree trunks. Apparently if you look closely, you can also find random dive equipment accidentally dropped in the cenote!

Since we were almost 120 feet deep at this point, we couldn’t linger long due to safety limits, so after a few minutes we began our ascent. Passing through the hydrogen sulfide layer again felt mildly terrifying, but knowing what awaited me on the other side helped ease my nervousness.

Once we were back above the hydrogen sulfide layer, we could see the tree branches jutting from the cenote’s bottom, which made for an eerie sight. We then continued our gradual ascent all the way back to the top, looping around the cenote.

Angelita is without a dout one of the most unique and intense dives I’ve ever had the pleasure of experiencing. I’d put it up there as my second favorite cenote dive after The Pit. While The Pit evoked more awe 🤩, I would say that Angelita evokes more of a thrill 😱.

Carwash (Aktun Ha)

Cenote Carwash—aptly named because localys used to wash their cars here before it became a well-known spot for snorkeling and scuba diving—was a memorably conclusion to our scuba diving trip. Despite attempts to change the name to “Aktun Ha” (”water cave” in Mayan), the original nickname stuck.

The cenote features a large open area with some turtles as well as a crocodile off to the corner. It’s normally full of snorkelers, however, during our visit at the end of May the top layer of the water was quite murky, limiting visibility to only the scuba divers underneath. Despite that, diving below the surface revealed a crystal-clear underwater world, full of fish and underwater lilypads, making it feel like we were in a massive aquarium.

Spotted this cave diving sign on our dive route!

After swimming with the fish, we soon started descending into cavern encircling the large open area where large stalactites hung from the ceiling. Although the stalactites were fascinating, the main highlight of the dive was the marine life. Out of all the cenotes we explored, this one takes the cake for most vibrant aquatic life.